Transcript

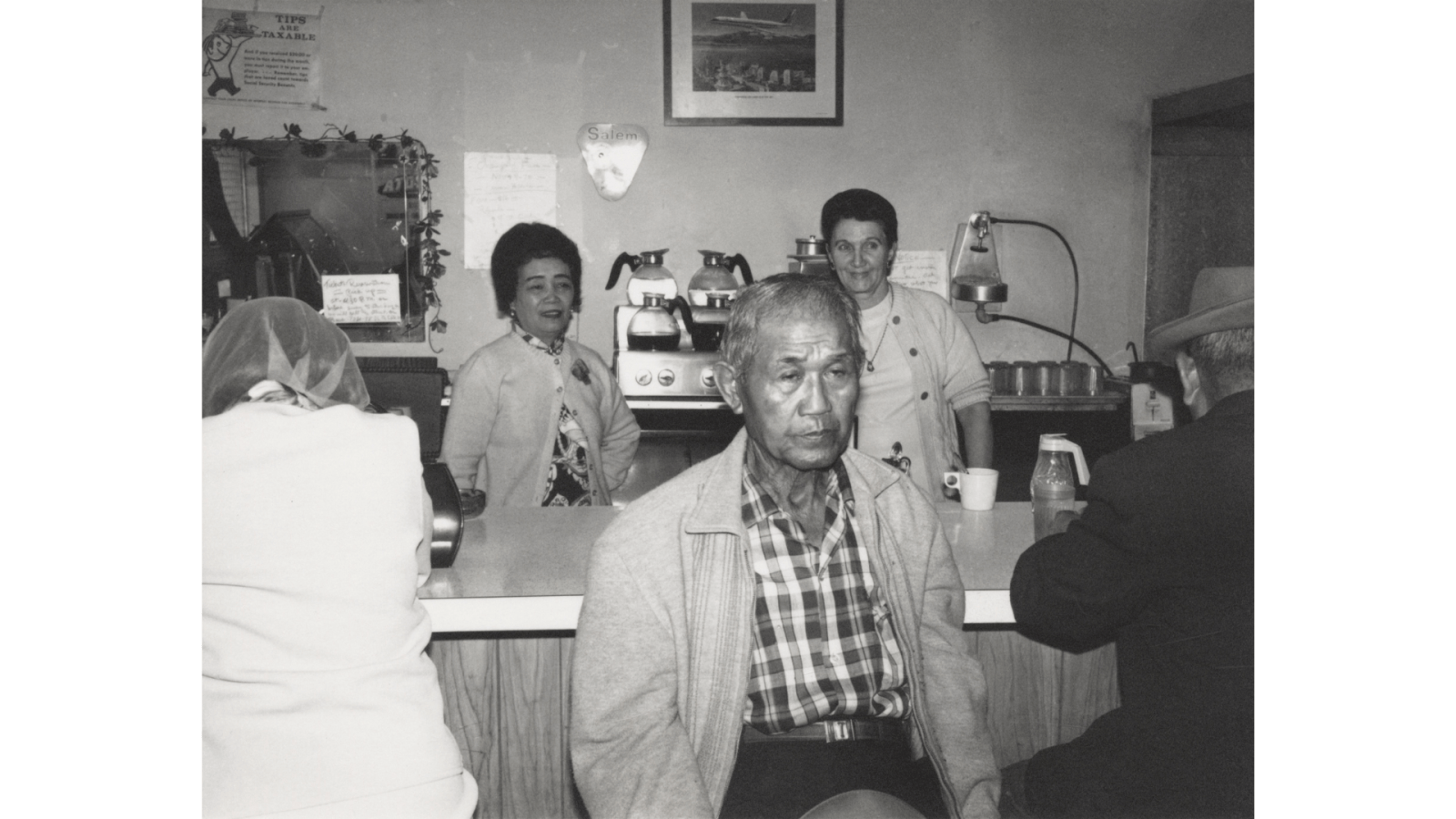

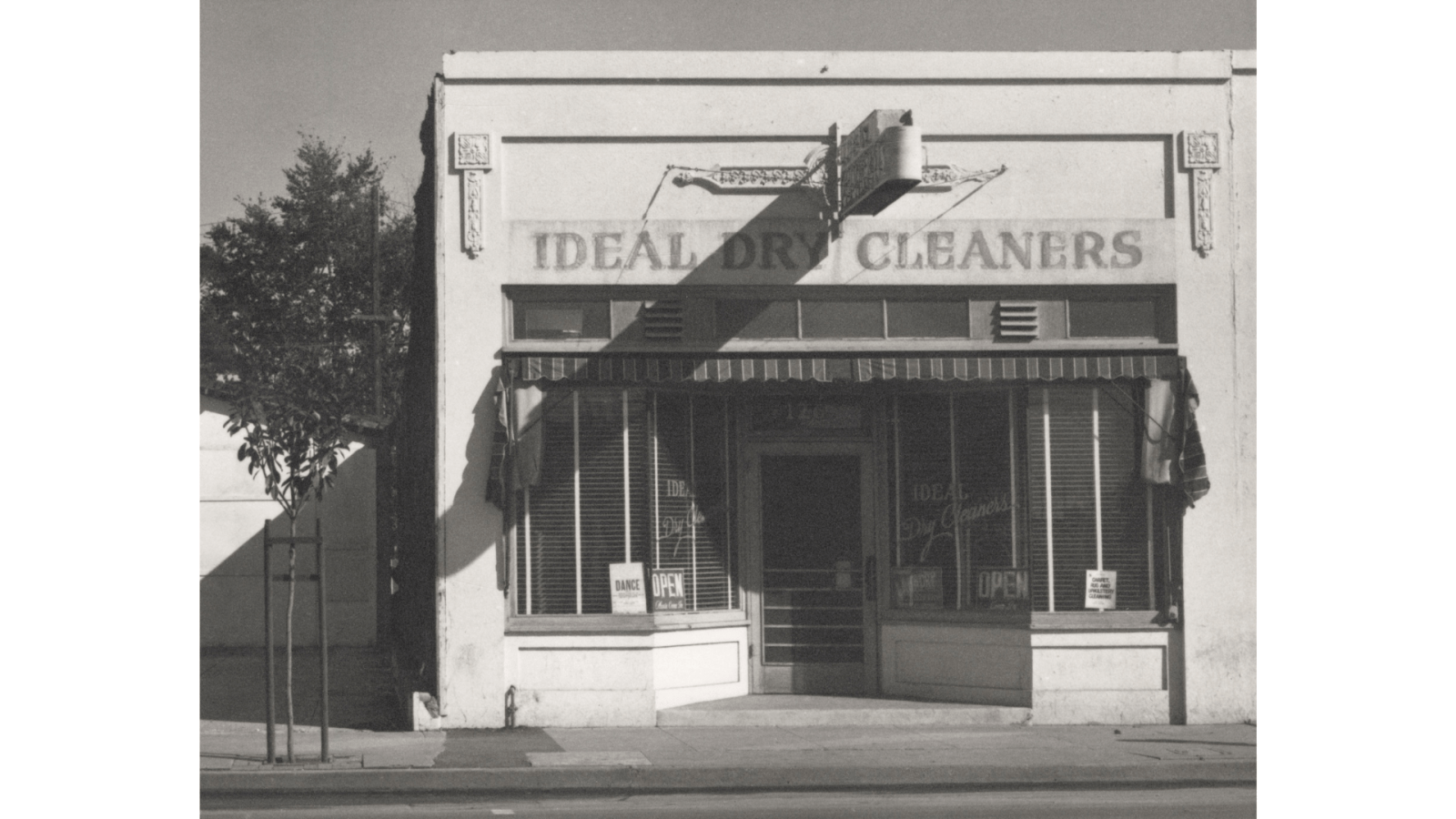

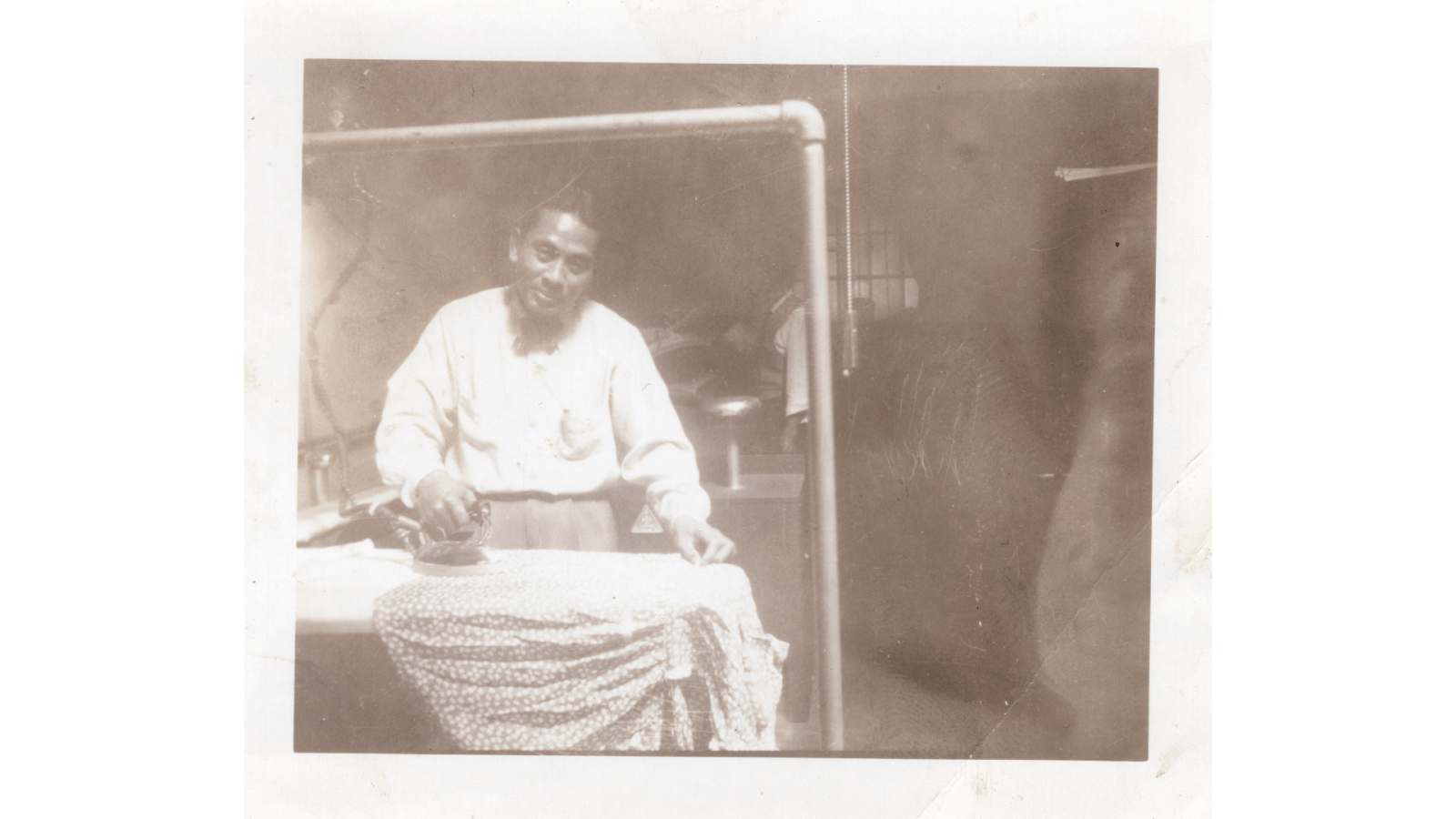

The Pajaro Valley Filipino American community is diverse, and the experiences of its members have been shaped by where they live. For those living in the Watsonville city limits, commercial enterprise and non-agricultural work could be more of a daily reality. Ethnic-owned businesses lined Main Street through downtown Watsonville. For those living in more rural areas of the Pajaro Valley, field labor structured the day-to-day, even for the young children of manong and manang.

This section of the exhibition offers windows into these experiences. Connie Zheng’s multimedia map features Filipino American sharecroppers who lived in the outskirts of Watsonville. Also featured here are a series of photographs representing Filipino-owned businesses formerly based on Main Street. While owning businesses offered opportunities to interact with the greater Watsonville community, many shop owners continued to work long hours to support their families. Lastly, Ant Lorenzo’s installation discusses the experiences of the DeOcampo family who grew up on the fields in Aromas. We’ve paired these two interviews to demonstrate how class and geography shaped the experiences of Filipino American children in the Pajaro Valley.

Eva Alminiana Monroe

Lower Main, or the neighborhood south of Main Street in downtown Watsonville, was once home to many Filipino-owned businesses. Members of the Filipino community frequented these successful institutions, and for many of our oral history narrators, these places helped make Watsonville home. In this clip, Eva Alminana Monroe discusses the opportunities she experienced as the daughter of Amando Alminiana, the owner of Universal Barbershop. Amando saw the barbershop as a meeting ground for the region’s diverse populations. Among her recollections, Eva shares memories visiting Universal Barbershop, to drop off her dad’s baon–or packed food–to help him get through the busy day.

My Father worked that barbershop from like, eight in the morning till eight at night. Pretty much twelve hours. And he would bring a lunch. He would bring a baon that my mother would pack for him and he would heat it up in the back because he had a little kitchen in the back too. […] When I wasn’t in school, I could ride my bike from our house, which was probably about eight to ten blocks away, right up Bridge Street and bring my father his baon and then just kind of hang out in the barbershop listening to what everybody had to say. And then I would hang out because all the manongs who were in there had no children. And so, if a child would show up: oh they’d dig out the candy out of their pockets, they’d give you quarters and fifty cents and if they’re feeling really lush, a dollar. So I got to know a lot of these wonderful old men, and from the barbershop. […] That was his big business, entrepreneurship: his little barbershops. But it was enough to send us all to school, to pay for our educations, to give us help with our down payments for our houses.

Antoinette DeOcampo-Lechtenberg

During our interview with Antoinette, the daughter of Paul and Gloria DeOcampo, Antoinette offered us a view of the Pajaro Valley from the perspective of a child who once worked in the fields. In this clip, Antoinette, who was raised in rural Aromas, discusses how her childhood differed from that of other children who grew up in Watsonville.

I think my first job was folding boxes in the garage because we had a little farm stand in the garage, and I think it was like three or four. But, you know, we were always in the field. And then it went to picking up strawberry runners when the fields were strawberries. My sister and I moved irrigation pipes. We were up at dawn and outside; working, picking whatever we were growing at the time. We had green beans, strawberries, tomatoes, cucumbers—cucumbers we did for a lot of years. […] We were just little and of course it was fun because, you know, we thought, okay—for me folding boxes was fun and got me what, five cents or three cents a box. And as you grew up, it got a little bit less fun. [laughs] Because it was hard work. And it was work. We worked every summer. Come home from school, you went out in the field and you work because it was necessary. When we got older, we got work permits and we went to other farms. I mean, it was all agriculture around us. […] And it was farm work. It was work.